Researchers from Penn State and Pennsylvania-based EC Power say they’ve developed a lithium-ion battery that heats itself if the temperature is below 32 degrees F. According to the researchers, this technology would have the most impact on relieving winter “range anxiety” for electric vehicle (EV) owners.

“It is a long-standing problem that batteries do not perform well at subzero temperatures,” says Chao-Yang Wang, professor of materials science and engineering and director of the Electrochemical Engine Center. “This may not be an issue for phones and laptops but is a huge barrier for electric vehicles, drones, outdoor robots and space applications.”

Conventional batteries at below-freezing temperatures suffer severe power loss, which leads to slow charging in cold weather, restricted regenerative breaking and reduction of vehicle cruise range by as much as 40%, say the researchers. These problems require larger and more expensive battery packs to compensate for the cold.

“We don’t want electric cars to lose 40 to 50 percent of their cruise range in frigid weather, as reported by the American Automobile Association, and we don’t want the cold weather to exacerbate range anxiety,” continues Wang. “In cold winters, range anxiety is the last thing we need.”

Relying on previous patents by EC Power, the researchers say the all-climate battery weighs only 1.5% more and costs only 0.04% of the base battery price. They also designed it to go from -4 degrees F to 32 degrees F within 20 seconds, and from -22 degrees F to 32 degrees F in 30 seconds while consuming only 3.8% and 5.5% of the cell’s capacity, respectively. They claim this is less than the 40% loss that is typical in conventional lithium-ion batteries.

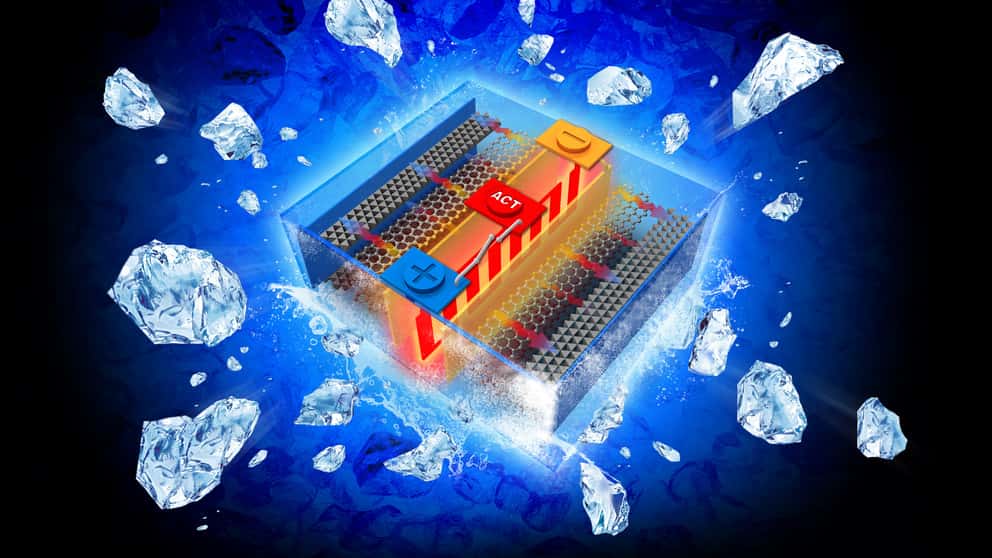

The all-climate battery uses a 50-micrometer-thick nickel foil with one end attached to the negative terminal and the other extending outside the cell to create a third terminal. A temperature sensor attached to a switch causes electrons to flow through the nickel foil to complete the circuit. The researchers say this rapidly heats up the nickel foil through resistance heating and warms the inside of the battery. Once the battery is at 32 degrees F, the switch turns off and the electric current flows in the normal manner.

Although other materials could also serve as a resistance-heating element, nickel is low cost and works well, the researchers add.

“Next, we would like to broaden the work to a new paradigm called SmartBattery,” says Wang. “We think we can use similar structures or principles to actively regulate the battery’s safety, performance and life.”